Misinformation

in the media and social networks: A violation of migrants’ rights

Desinformación en los medios de

comunicación y las redes sociales: una violación a los derechos de los

migrantes

Carolina Y. Andrada-Zurita

Correspondencia: carolina.andrada@uns.edu.ar

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7870-4188

Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina.

Recibido: 20/02/2025

Aceptado: 21/04/2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24265/cian.2025.n21.06

Para citar este artículo:

Andrada-Zurita, C. Y. (2025). Misinformation in the media

and social networks: A violation of migrants’ rights. Correspondencias & Análisis, (21), 168-186. https://doi.org/10.24265/cian.2025.n21.06

Abstract

This research was conducted using a qualitative

methodology with a descriptive scope. A documentary review was carried out of

the texts of Laws 23.592, 24.515, and 25.871 from Argentina to identify

strategies used to curb the spread of false information in the media. Academic

articles and reports by international organizations (IOM, IEO, UN) were also analyzed.

Among the most important findings is the difficulty of fully enforcing

regulations without risking cases of censorship, which often leads to moral

dilemmas. The real implications include the need to protect migrants’ rights

from the dissemination of false information that affects them, as well as

addressing any accusations of censorship. At the same time, this includes

carrying out actions that allow awareness not only to journalists and

communicators, but also to the general public about the importance of managing

the good use of information and not to replicate information that is known to

be false, distorted or doubtful.

Keywords: Disinformation,

media, social networks, migrants, human rights, vulnerability

Resumen

Esta

investigación se llevó a cabo utilizando una metodología cualitativa con un

alcance descriptivo. Se realizó una revisión documental de las Leyes 23.592,

24.515 y 25.871 de Argentina con el objetivo de identificar estrategias

empleadas para frenar la difusión de información falsa en los medios de

comunicación. También se analizaron artículos académicos e informes de

organismos internacionales (OIM, IEO, ONU). Entre los hallazgos más relevantes

se encuentra la dificultad de aplicar plenamente las normativas sin incurrir en

posibles casos de censura, lo que con frecuencia plantea dilemas morales. Las

implicancias reales incluyen la necesidad de proteger los derechos de las

personas migrantes frente a la difusión de información falsa que las afecta,

así como abordar cualquier acusación de censura. Al mismo tiempo, esto implica

llevar a cabo acciones que promuevan la concientización no solo entre

periodistas y comunicadores, sino también con el público en general, sobre la

importancia de hacer un uso responsable de la información y de evitar replicar

contenidos que se sabe que son falsos, distorsionados o dudosos.

Palabras clave:

desinformación, medios de comunicación, redes sociales, migrantes, derechos

humanos, vulnerabilidad

Introduction

The right to migrate must be guaranteed, taking into

account principles such as universality and equality, which means that migrants

must be treated with respect for their customs and culture. Therefore, actions

by the media and social networks that violate the identity of migrants–such as

the dissemination of false information or content tainted by prejudice and

stereotypes–should be limited, as they ultimately misinform society and harm

this minority group. Likewise, mockery and humiliation constitute degrading and

unfair treatment of migrants.

As such, this research was

conducted following three main questions:

• How does

misinformation affect the rights of migrants?

• How can freedom of

expression be restricted when it generates disinformation?

• To what extent does

the right to freedom of expression conflict with the right to cultural identity

and/or the right to non-discrimination?

Respect for the culture of

migrants and the media

Within the framework of cultural rights, which are

part of human rights and as stated in the Fribourg Declaration (United Nations,

2007), these must be guaranteed without discrimination–that is, regardless of

sex, colour, religion, language, national or ethnic

origin, political convictions, social status, or any other cultural

characteristic of the person. In the same vein, the Inter-American Principles

on the Human Rights of All Migrants, Refugees, Stateless Persons and Victims of

Human Trafficking (2019) call for non-discrimination, equal access to justice,

and the protection of human rights in general. Respect for the identity of

migrants is essential; however, this is often not reflected in practice,

particularly on social networks and in the media, where such identities are

frequently attacked out of prejudice and misinformation (Pennycook & Rand, 2022;

Zilinsky et al., 2024).

The recently disappeared National Institute against

Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism (INADI) of Argentina, carried out in this

country investigations on a news channel, which in the coverage of the G20

summit held in the city of Buenos Aires in 2018, the participants were treated

in a discriminatory manner. This leads us to ask, from a rights-based

perspective, to what extent the right to freedom of expression (John, 2018; Mastrini, 2011) conflicts with the right to cultural

identity and/or the right to non-discrimination. While individuals may exercise

their right to free expression, in cases where this right is exceeded, legal

action may be pursued, such as for slander or defamation. The Crónica TV channel is well known in Argentina

because it captures the attention of viewers through humorous or doublemeaning headlines. However, it has sometimes crossed

certain boundaries in that what is communicated ceases to be funny or amusing,

to become offensive. During the G20 Summit,

as mentioned above, the newscast made a series of jokes about several world

leaders that were described by the audience as pejorative and tasteless.

The following image retrieved

by Iprofesional (2018) exemplifies this:

From Iprofesional (2018)

(https://www.iprofesional.com/legales/282397-El-INADI-investiga-las-polemicas-placas-de-Cronica-TV-sobre-el-G20)

The image is an allusion to the arrival of the Indian

leader, compared to the character in the cartoon comedy The Simpsons.

Migrants also often suffer some violation of their

rights by the media when biased information is provided by prejudice and

stereotypes (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2018);

as well as when immigration is assumed to be a problem. Therefore, the media

must be careful with the messages they convey (Georgiou, 2013) and the social

representations they establish (Mannarini et al.,

2020; Orr & Husting, 2018), as these can generate social paranoia and lead

the public to adopt a negative attitude toward migrants, perceiving them, in

some way, as enemies (Santamaría, 2017; Tsoukala, 2017).

There is also often a lack of understanding about how

people’s rights are guaranteed. The fact that the State guarantees access to

and enjoyment of rights by immigrants’ does not indicate that it restricts the

rights of the rest of the population of the country. The foundations of such

ideas often arise from misinformation that circulates in society (Ecker et al.,

2022). Yet, the cultural rights of migrants are affected and violated when they

are treated as the «other» (Bailey & Harindranath,

2005) and marginalized by restricting all types of freedoms that they understand.

In this respect, we must note that cultural rights, as

indicated in the IberoAmerican Cultural Charter, are

fundamental rights (Ninth Ibero-American Conference

of Culture, 2006). Within this framework, individuals should be able to develop

their creative abilities, participate, and be included. However, one key aspect

we must consider is that we are currently shaped by telecommunications and new

technologies (including social networks), and the misuse of these tools may

affect and violate such rights. Technologies mediate individuals with reality

and in turn establish a new reality when they develop narratives that relate

migrants to economic problems, criminal acts and/or terrorism (Esses, 2021). In contrast, the media should collaborate in

the struggle to uphold and respect human rights (Moore-Berg et al., 2022).

The other side of social media

In social media people are aware of their feelings and

thoughts. Sometimes users express violence and contempt towards the «other»,

which is evident in debates and discussions that are generated in such a medium

(Ekman, 2019). In a way that seems less hostile, it is also attacked through

the humor condensed into images that circulate online and are commonly known as

memes. While we can find images based on innocent humour, many of them also

contain elements of resentment and reflect homophobic, xenophobic, racist, or

classist prejudice, among others.

Migrants are often caught up in this aggressive humor which affects and

violates their rights, installing and disseminating false information about

their customs and beliefs very quickly, something which is difficult to correct

(Johnson & Seifert, 1994). This denotes two issues: on the one hand, the

manifestation of hatred as such and non-acceptance of a different culture; on

the other hand, the setting of a limit, or rather an exclusion line, which is

usually validated by violence.

Migrants have sometimes been placed on an equal

footing with criminals, terrorists and rapists, and they have been incited in a

figurative way to attack them. The messages conveyed, thus, in totally

condemnable terms, denote a certain superiority which is falsely believed to

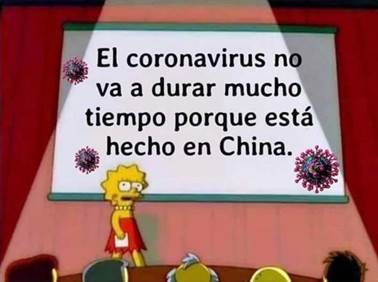

exist between one nationality and another. Even during the pandemic of

COVID-19, Twitter was the scene of a large number of xenophobic posts on this

subject, since this event was used as an excuse to blame the Chinese migrants

for the presence of the virus, triggering acts of violence in some cases (Luna,

2020).

Even the graphic medium Clarín echoed certain images that

it called «creative ideas circulating on networks and put a little humor to the

isolation by COVID-19» (Clarín,

2020, para. 1). Perhaps they did not notice that what might at first sight be

funny in fact reflected a prejudice towards the Chinese community about the

products coming from their country of origin (or what they produce in general)

being of poor quality and short duration. The following is one of these images:

Coronavirus in the networks: memes and plates to pass the quarantine

Also, it is possible to observe in platforms like

Facebook, where it is common for digital newspapers to share their news, how many

Internet users are encouraged to participate with their comments and opinions,

which in many cases converge on attacks towards that «other different» (Rauch

& Schanz, 2013). We are referring primarily to

publications related to migratory phenomena, LGBTIQ+ pride marches, claims of

indigenous peoples, as well as any information pertaining to cultural

minorities (Dubrofsky & Wood, 2014). There is

something worrying here, and it is the fact that this hatred expressed on

social media is sustained in «real life» or, better said, «off line», since it

seems that at times people will split up and live two different lives: virtual

and real (Andrada-Zurita, 2023). Regardless of the

context in which an assault takes place, it remains an act of

aggression–whether carried out in person or through any medium, including

social media. This is especially concerning when it incites collective hatred

against a minority group, which is already vulnerable and exposed by such

practices.

It is therefore necessary to adopt measures (Pennycook et al., 2021)

that contribute to reduce these hate-motivated actions that are disseminated

through social networks, in order to guarantee the rights of migrants,

particularly non-discrimination and cultural identity (Dervin,

2012).

Methods

Our research was guided by three research questions,

already mentioned in advance. The initial question was: How does misinformation

affect migrants’ rights? In other words, how can the dissemination of false or

biased information lead to the violation of migrants’ rights. A second question

was: how can freedom of expression be restricted when it generates

misinformation? This question addresses the notion that, although freedom of

expression is a fundamental right that should not be arbitrarily restricted, it

may require certain forms of «regulation» when it infringes upon the rights of

others. Finally, a final question was: To what extent does the right to freedom

of expression clash with the right to cultural identity and/or the right to

nondiscrimination? The aim of this final question is to clarify how violations

of freedom of expression may affect the cultural identity of migrants through

certain expressions, as well as foster situations of discrimination that are

reprehensible.

To answer these questions, we used a qualitative

methodology and a descriptive scope (Bryman, 2016). The study focused on the

classification and analysis of academic articles, as well as reports made by

international organizations such as the International Organization for Migration

(IOM), the Organization of Ibero-American States for

Education, Science and Culture (OEI) and the United Nations (UN). Additionally,

the study focused on the current national legislation, particularly Law 23.592

on discriminatory acts, Law 24.515 establishing the National Institute against

Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism, and Law 25.871 on migration; they are

closely related to the subject matter addressed and allow us to compare those

situations in which the rights of migrants as established therein are violated.

In other words, these laws establish a framework from which to operate, they

set the boundaries that must not be transgressed and the actions that will be

carried out in case of any violation of migrants’ rights.

Given that the aim is to highlight the relationship

between discourses transmitted through media and social networks with

disinformation, the policies adopted in response, the existing laws in this

field and their impact on the guarantees of cultural rights for migrant

populations, this study offers an assessment that will attempt to interpret the

phenomena in their natural state (Merriam, 2009), covering the period from 2013

to 2023.

Certainly, as this is not a case study involving the

selection of a specific population sample on which empirical work is done, but

rather a documentary analysis, that is to say, a theoretical study as mentioned

above. This approach allows for greater flexibility, which is advantageous as

it enables the exploration of related issues within the same field of study and

broadens the scope of the research itself. As a research technique, document

analysis involves the study and interpretation of documents relevant to

specific research, and in this case, it is combined with a critical research

perspective. Following Richard Yin (2013), we evaluate not only the content of

the texts, but their context and meaning.

By referring to the study and analysis of the selected

texts, as well as to the available data on the matter, we were able to

establish connections between them which allowed to determine the adequacy of

the legislation in force in Argentina. At the same time, it allowed us to

identify which similar strategies are been deployed worldwide to combat

disinformation, both in social networks and media; since they are among the

main factors of migrants’ rights violations worldwide. This in turn allows us

to affirm that both the methodology employed and the techniques of data

collection and analysis carried out, were appropriate for our research and the

results obtained.

Results

We start from the theoretical background and raise

three questions that are key to develop how disinformation violates migrants’

rights:

1) How does misinformation affect

the rights of migrants?

The media influence how

society perceives migrants and their image, constituting a positive or negative

view depending on the characterization of the society and the message that it

seeks to convey. This message responds to stories and speeches supported by a

particular ideology (Caldas-Coulthard, 2003).

How to combat disinformation from the classroom

To use Engels’ terms, humans

are different from animals both by work and by language (Engels, 1973). Marx

and Engels (1977) also consider language to be the main means by which man

develops knowledge in order to appropriate nature. Culture, then, is the result

of the cumulative growth in human power over nature, which encompasses language,

thought, knowledge and even tools and working practices. Such a culture,

although it may present certain variations in its constitution, will pass from

one generation to another as if it were a sort of second nature to humankind.

The question of language as a

means of transmitting culture in an anthropological sense allows us to ask

whether it can become an instrument that distorts the material conditions

already mentioned. Stuart Hall (1992) points out that through language men

«elaborate stories and explanations, with which they give meaning to their

‘world’ and become aware of it», and thus questions: «Does it also bind and

work them instead of freeing them? How can thought conceal aspects of their

real conditions instead of clarifying them? » (p. 291).

Another relevant concept is

that of ideology, which according to

Hall (1992) has «a decentralizing and displacing effect on the free development

processes of ‘human culture’» (p. 284). Ideology is a set of dominant ideas; in

turn, the dominant material relations, embodied in a ruling class, determine

the extent and scope of an epoch. As Marx and Engels (1977) point out, the

domination is carried out by producers of ideas, by thinkers who regulate the

production and distribution of the ideas of their time. Althusser (1968) also

points out that, while ideologies are usually made up of systems of

representations, concepts and images, they impose themselves on men as

structures. In this sense, ideology is not defined by what is thought, but by

what is lived or experienced–that is, by the way individuals relate to their

conditions of existence. This is closely related to the idea that the media

influence how migrants are perceived and the prejudices that develop around

them. It stresses that both language and ideology are always present in the

speeches and messages conveyed through such media. They will be beneficial or

disadvantageous depending on the intentions of those who communicate and those

behind the management of media outlets. In this context, we can say that public

opinion will be somewhat shaped by the messages that are introduced in media

discourse, even if this includes disinformation.

2) To what extent does the right

to freedom of expression conflict with the right to cultural identity and/or

the right to non-discrimination?

When the exercise of freedom

of expression transgresses certain socially defined limits–where it manifests

as disrespect or disloyalty toward other members of society–this right may be

overridden by other rights, such as the right to nondiscrimination and the

right to cultural identity. This undoubtedly includes a violation of the rights

of an «other» who believes himself to be different and is therefore belittled,

either through the dissemination of false information and/or a type of

aggressive humour that is disseminated via different forms of media, including

social networks. This is why it is necessary to establish awareness campaigns,

where individuals are properly informed about certain practices included in

what is known as freedom of expression, but which may be counterproductive to

other individuals, causing significant harm. The focus here should be

emphatically placed on the concept of responsibility,

both at individual and collective levels, in relation to the use of information

and, in its absence, the disinformation established in society at large.

Such campaigns could aim to

raise awareness through different means, such as pamphlets, reels on social

media, and videos broadcast on television channels. They could also target the

educational level through intercultural education programs promoted by the

Ministry of Education, including training for teachers and other professionals.

The media can promote positive representation of immigrants, highlighting their

contributions or achievements, as well as establishing guidelines for

responsible and ethical journalism when addressing immigration related issues.

Undoubtedly, to carry out this kind of campaign, it is necessary to involve

different sectors of society, not only the political leadership sector but also

education, the media and the community itself, in order to achieve a

significant impact.

Both in Argentina and abroad,

there are regulations that reduce acts of hatred and discrimination against

migrants. This also applies to the transmission and dissemination of

information which is permeated with false data.

In Argentina, article 1 of Law

23.592 states that anyone who commits «discriminatory acts or omissions

determined on grounds such as race, religion, nationality, ideology, political

or trade opinion, sex, economic status, social condition or physical characteristics»

(Law 23.592, 1988, art. 1, para. 2), shall cease such action and make good the

moral and material damage caused. The National Institute against

Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism (INADI), which was dissolved in August

2024 for almost three decades, was also responsible for the preparation of

«National policies and concrete measures to combat discrimination, xenophobia

and racism, promoting and carrying out actions to this end» (Law 24.515, 1995,

art. 2, para. 2).

In 2017, the Argentine

government launched a campaign to raise awareness of the issue, which had a

great impact on society, known as «I am a migrant», also carried out at global

level to combat racism, discrimination and xenophobia against migrants. This

work aimed to «dismantle discourses that discriminate» (OIM, 2017, para. 10).

In 2020, 21 regional forums

were held with the participation of 1694 organizations from all over Argentina.

In addition, the governments of each province were consulted on the problems

and policies implemented in each jurisdiction, this shows the interest in

overcoming the situations of violence that are gestating in society against

existing minorities in the country, including migrants. This is why we work on

the development and implementation of policies aligned with the problem at

hand, which is very necessary (Kozyreva et al.,

2024).

In conclusion, we can say that while there is a

normative framework in Argentina responsible for guaranteeing and safeguarding

the rights of migrants, one must pay attention to promoting a respectful use of

social networks (Andrada-Zurita & Manrique Quirós, 2022), as well as the information conveyed by the

media.

Still image from the video Somos migrantes (2023)

Note. From OIM Argentina

(2023) (https://argentina.iom.int/es/news/el-inadi-yoim-argentina-lanzaron-la-campana-somos-migrantes)

Conclusion

Historically, migration has had a significant

relevance in Argentina and still has it today, with more than two million

inhabitants of foreign origin, mainly from neighbouring

countries. Domestic regulations uphold and protect the rights of migrants, so

that the text of the Migration Law 25.871 recognizes the human right to migrate

and supports equal access to public goods, social services, employment, health,

education, justice and social security in the same way as native citizens.

Therefore, to combat any act of discrimination against migrants within society,

appropriate measures must be implemented.

However, the media have repeatedly transmitted

inaccurate or misleading information, which contributes to the emergence and/or

persistence of prejudices that affect this type of minority group and violate

their rights. Therefore, it is imperative that the State emphasize the

importance of making a conscious and responsible use of the information

transmitted.

Regarding social networks, in the dissemination of

degrading, aggressive and xenophobic and/or racist content, strategies to

prevent such actions are more difficult, but this does not mean that they are

impossible to formulate and implement. An example of this is that, in addition

to legal instruments, the state promotes multiple awareness campaigns which

contribute significantly to the responsible use of social media and to the

rectification of misinformation when necessary. This highlights the commitment

of the Argentine State to guaranteeing the rights of migrants.

Conflicto de intereses

La autora declara que no existe ningún tipo de conflicto de intereses.

Responsabilidad

ética

Se ha

citado correspondientemente toda la bibliografía empleada para la realización

del artículo, así como también, las imágenes.

Contribución

de autoría

CAZ: la

autora declara ser responsable por la totalidad de la investigación y

elaboración del artículo.

Financiamiento

El

presente artículo no tuvo ninguna fuente de financiamiento y se realizó con

recursos propios de la autora.

Declaración

sobre el uso de LLM (Large Language Model)

Este

artículo no ha utilizado para su redacción textos provenientes de LLM (como

ChatGPT u otros).

References

Althusser, L. (1968). Reading capital. New Left Books.

Andrada-Zurita, C. Y. (2023). Lo

evanescente. Ensayo sobre la cultura de la cancelación y sus formas de

violencia. Imprenta de libros.

Andrada-Zurita, C., & Manrique Quirós, M. F.

(2022). Discriminación, xenofobia y vulneración de los derechos de los

migrantes. In P. E. Slavin & J. Tumini (Dir), L. Escalante, L.

Martínez, L. López (Comp.), Debates en

Filosofía y Ciencia Política 2022: XXII Jornadas Internacionales en Filosofía y

Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales (pp. 32-41). Universidad Nacional de Mar de

Plata.

Bailey, O. G., & Harindranath,

R. (2005). Racialised ‘othering’: the

representation of asylum seekers in the news media. In S. Allan (Ed.), Journalism: critical issues (pp.

274-286). Open University Press.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford

University Press.

Caldas-Coulthard,

C. R. (2003). Cross-cultural representation of ‘otherness’ in media discourse.

In G. Weiss & R. Wodak (Eds.), Critical discourse analysis: Theory and

interdisciplinarity (pp. 272-296). Palgrave

Macmillan Ltd.

Clarín (2020, March 20). Coronavirus en las redes: memes y placas

para pasar la cuarentena. https://www.clarin.com/internacional/coronavirus-redes-memes-placas-pasarcuarentena_0_g69dxJVAY.amp.html

Dervin, F. (2012). Identidad cultural, representación y

alteridad. In J. Jackson (Ed.), The Routledge

handbook of language and intercultural communication (pp. 195-208).

Routledge.

Dubrofsky, R. E., &

Wood, M. M. (2014). Posting racism and sexism: Authenticity, agency and

self-reflexivity in social media. Communication

and Critical/Cultural Studies, 11(3),

282-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2014.926247

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky,

S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N.,

Kendeou, P., Vraga, E. K.,

& Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological

drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

Ekman, M. (2019).

Anti-immigration and racist discourse in social media. European Journal of Communication, 34(6), 606-618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323119886151

Engels, F. (1973). The part

played by labour in the transition from ape to man.

In K. Marx & F. Engels, Selected

Works. Vol. 3 (pp. 66-77).

Progress Publishers.

Esses, V. M. (2021).

Prejudice and discrimination toward immigrants. Annual Review of Psychology, 72,

503-531. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-080520-102803

Georgiou, M. (2013). Diaspora

in the digital era: Minorities and media representation. Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 12(4), 80-99. https://www.ecmi.de/fileadmin/downloads/publications/JEMIE/2013/Georgiou.pdf

Hall, S. (1992). Cultural studies and its theoretical

legacies. In L. Grossberg, C. Nelson

& P. Treichler (Eds.), Cultural Studies (pp. 277-294). Routledge.

Impulso_06. Formación y Futuro. (n. d.). Cómo combatir la desinformación desde el

aula. https://impulso06.com/como-combatir-la-desinformacion-desde-el-aula/

Instituto Nacional contra la Discriminación, la

Xenofobia y el Racismo INADI. (2020, June 5). El racismo estructural en los medios. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/el-racismoestructural-en-los-medios

Instituto Nacional contra la Discriminación, la

Xenofobia y el Racismo INADI. (2022, May 26). Nuevo Mapa Nacional de la Discriminación. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/el-inadi-presenta-el-nuevo-mapa-nacional-de-la-discriminacion

Inter-American Commission on

Human Rights-IACHR & Organization of American States-OAS More rights for

more people. (2019, December 7). Inter-American Principles on the Human

Rights of All Migrants,

Refugees, Stateless Persons and Victims of Human Trafficking [Resolution

04/19]. https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/decisions/pdf/Resolution-4-19-en.pdf

Iprofesional.

(2018, November 30). El INADI investiga las polémicas

placas de Crónica TV sobre el G20. https://www.iprofesional.com/legales/282397-El-INADI-investiga-laspolemicas-placas-de-Cronica-TV-sobre-el-G20

John, R. (2018). Freedom of

expression in the digital age: A historian’s perspective. Church, Communication and Culture, 4(1), 25-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/23753234.2019.1565918

Johnson, H. M., & Seifert,

C. M. (1994). Sources of the continued influence effect: When misinformation in

memory affects later inferences. Journal

of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory,

and Cognition, 20(6), 1420-1436. https://doi.org/10.1037/02787393.20.6.1420

Kozyreva, A., Lorenz-Spreen, P., Herzog, S. M, Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S.,

Hertwig, R., Ali, A., Bak-Coleman,

J., Barzilai, S., Basol, M., Berinsky,

A. J., Betsch, C., Cook, J., Fazio, L. K., Geers, M., Guess, A. M., Huang, H., Larreguy,

H., Maertens, R., Panizza, F., … Wineburg,

S. (2024). Toolbox of individual-level interventions against online

misinformation, Nature Human Behaviour, 8,

1044-1052. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01881-0

Law

23.592. (1988). Actos Discriminatorios.

Argentina.gob.ar. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/normativa/nacional/ley-23592-20465/actualizacion

Law

24.515 (1995). Instituto Nacional contra la Discriminación, la Xenofobia y el

Racismo. Creación, objeto y Domicilio. Atribuciones y Funciones. Autoridades.

Recursos. Disposiciones Finales. Argentina.gob.ar. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/normativa/nacional/ley-24515-25031/texto

Law

25871. (2004). Ley de Migraciones. https://www.migraciones.gov.ar/pdf_varios/campana_grafica/pdf/Libro_Ley_25.871.pdf

Luna, M. (2020, February

26). «¿Qué hacés, coronavirus?»: la broma de mal gusto que terminó en una

brutal pelea en un supermercado chino. Infobae.

https://www.infobae.com/sociedad/2020/02/26/que-haces-coronavirus-la-broma-de-mal-gusto-que-termino-en-unabrutal-pelea-en-un-supermercado-chino/

Mannarini, T., Veltri, G. A., & Salvatore, S. (2020). Media and social representations of therness. Springer International Publishing.

Marx, K., & Engels, F.

(1977). The German Ideology. Lawrence

& Wishart.

Mastrini, G. (2011).

Argentina: Media system. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of

Communication. John Wiley & Sons, Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbieca052.pub2

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and

implementation. JosseyBass.

Moore-Berg, S. L., Hameiri, B., & Bruneau, E. G. (2022). Empathy,

dehumanization, and misperceptions: A media intervention humanizes migrants and

increases empathy for their plight but only if misinformation about migrants is

also corrected. Social Psychological and

Personality Science, 13(2),

645-655. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211012793

Ninth Ibero-American

Conference of Culture. (2006, July 13-14). Iberoamerican

cultural charter. Montevideo. https://derechodelacultura.org/archivos/13537

OIM/IOM Argentina. (2017, September

29). «Soy migrante» se presenta en Argentina: la OIM y el INADI se unen contra

la discriminación, la xenofobia y el racismo. ONU Migración. https://www.iom.int/es/news/soy-migrante-se-presenta-en-argentina-la-oim-y-el-inadi-seunen-contra-la-discriminacion-la-xenofobia-y-el-racismo

OIM/IOM Argentina. (2019, September

6). 40.o Fiesta Nacional del Inmigrante. https://argentina.iom.int/es/news/40deg-fiesta-nacional-del-inmigrante

Orr, M., & Husting, G.

(2018). Media marginalization of racial minorities: «Conspiracy theorists» in

U.S. ghettos and on the «Arab street». In J. E. Uscinski

(Ed.), Conspiracy theories and the people

who believe them (pp. 82-93). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190844073.003.0005

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D.

G. (2022). Accuracy prompts are a replicable and generalizable approach for

reducing the spread of misinformation. Nature

Communications, 13(1), 2333. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30073-5

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A.,

Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce

misinformation online. Nature, 592, 590-595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03344-2

Rauch, S., & Schanz, K. (2013). Advancing racism with Facebook:

Frequency and purpose of Facebook use and the acceptance of prejudiced and egalitarian

messages. Computers in Human Behavior,

29(3), 610-615. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/computers-inhuman-behavior/vol/29/issue/3

Roozenbeek,

J., & van der Linden, S. (2018). The fake news game: Actively inoculating

against the risk of misinformation. Journal

of Risk Research, 22(5), 570-580.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2018.1443491

Santamaría, C. C. (2017).

‘Build That Wall!’: Manufacturing the enemy, yet again. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(10), 999-1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1312592

Tsoukala, A. (2017).

Looking at migrants as enemies. In E. Guild & D. Bigo

(Eds.), Controlling frontiers. Free

movement into and within Europe (pp. 161-192). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315259321

United Nations. (2007). Fribourg Declaration on Cultural Rights.

University of Fribourg. https://www.unifr.ch/ethique/en/assets/public/Files/declaration-eng4.pdf

Yin, R. (2013). Case study research and applications: Design

and methods. Sage Publications.

Zilinsky, J., Theocharis, Y., Pradel, F., Tulin, M., de Vreese, C., Aalberg, T., Cardenal, A. S., Corbu,

N., Esser, F., Gehle, L., Halagiera, D., Hameleers, M., Hopmann, D. N., KocMichalska, K.,

Matthes, J., Schemer, C., Štetka,

Strömbäck, J., Terren, L.,

… Zoizner, A. (2024). Justifying an invasion: When is

disinformation successful? Political Communication, 41(6), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2024.2352483

Carolina Y.

Andrada-Zurita

Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina.

Licenciada en Filosofía por la Universidad Nacional

del Sur y Licenciada en Relaciones Internacionales por Universidad Empresarial

Siglo 21, Argentina. Docente e investigadora en Universidad Nacional del Sur.

También es docente a cargo de diplomaturas y especialización en el Instituto de

Ciencias Empresariales y Sociales. Directora y Editora de Revista Pares.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7870-4188

© Los autores. Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional (CC - BY 4.0)